Can the American Revolution Be Justified In Light of Romans 13

Dan Duncan:

Good afternoon. This chandelier creates a glare on that clock, so Peter, you’re not going to know where you are on the time, so maybe that’s good. And it’s good to have all of you here. Before I introduce our speaker, let me just welcome all of you. Some of you I know are visiting. Well, our speaker, I think most of you know who he is, but for some of you who may not, Dr. Peter Lillback is the president of Westminster Theological Seminary in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Dan Duncan:

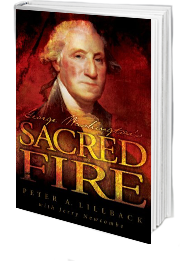

He is also a professor of historical theology there. So Peter has a good grasp of history. His specialty it seems is early American history. He wrote the book, George Washington’s Sacred Fire. Peter is also well versed in other areas of history. I know anthology, but the reformation and the theology of it. But before I say too much and steal some of Peter’s thunder or sacred fire for his introduction, I will turn it over to Peter. Oh, I do want to say this, after his lecture there will be time for questions and answers. Peter?

Dr. Peter Lillback:

Thank you.

Dan Duncan:

Thank you for being here.

Dr. Peter Lillback:

Thank you. Good to see you, Dan. Yeah, I can’t see the clock, but it’s never stopped me anyway. So you know. So we’re here, time doesn’t matter. Can you imagine this Saturday afternoon, and you came out at 4:00 o’clock and it’s sunny outside. This is amazing. It feels like you want to hear something, so let’s not worry about time and let’s just go for it, right?

Dr. Peter Lillback:

Basically, we’re going to just jump right into our study. So let me begin by saying that I am representing at this moment, the work that I have done for almost 20 years with a group called the Providence Forum. And the little booklet that you picked up today was the very first booklet we ever produced that ministry long before we even knew we’d have a book like George Washington and Sacred fire, just a little taste of how the idea providence runs through various expressions of American history.

Dr. Peter Lillback:

And so we hope you joy that, it was written way back in the time when George W. Bush was just getting ready to run for president. And that year, Philadelphia was the place where the Republican National Committee was being held. And so we went out and just passed these out to people on the streets. It was our way of saying welcome to Philadelphia. We want to know there’s a biblical story being behind all this thing. So that’s where it started. And we still have some in print, so we brought them down to share with you to give you a little taste about Philadelphia’s history.

Dr. Peter Lillback:

But we’re going to be looking at Romans 13 today. And the question that we’re going to be addressing is does Romans 13 stand as a condemnation of the birth of America through the American Revolution? Or is it an expression of why the American Revolution had a legitimate grounding? Can imagine this is a classic debate.

Dr. Peter Lillback:

And my discussion today, many of you might have the notes I’m going to use, and I’m going to follow those notes fairly closely because there’re a number of citations and arguments that make a sense. So I’m not preaching, I’m giving you more of a scholarly lecture today on that topic. But before we begin, let me read Romans 13 beginning at verse one on through about verse eight. So as we do that, let me open with prayer and then we’ll read this passage.

Dr. Peter Lillback:

Father, thank you for the joy of being at Believers Chapel here in Dallas. I thank you for this congregation that has been a place of blessing for me for many years, all the way back when I was a seminary student and enjoyed and learned under Dr. Johnson and his preaching and teaching. We thank you for its faithful witness, for your Word and for the ministry of Dan Duncan, as the preacher of the scriptures in this congregation. We thank you for the occasion that comes together for us, the ministry of the Providence Forum, sharing some of its to bring biblical witness to bear on the national story that we share as Americans. Would you bless this time and would you open your word to us and help us to understand things that might make us better citizens and more effective in engaging questions that are even pressing upon us at this moment in time. We thank you for all this and we pray it in Christ’s, amen.

Congregation:

Amen.

Dr. Peter Lillback:

Here’s the word of God, Romans 13 beginning at verse one. “Let every person be subject to the governing authorities. For there is no authority except from God, and those that exist have been instituted by God. Therefore, whoever resists the authorities, resist what God has appointed. And those who resist will incur judgment for rulers are not a terror to good conduct, but to bad. Would you have no fear of the one who is in authority? Then do what is good and you’ll receive His approval. For He is God’s servant for your good.

Dr. Peter Lillback:

But if you do wrong, be afraid for He does not bear the sword in vain. For He is the servant of God, an avenger who carries out God’s wrath on the wrong doer. Therefore, one must be in subjection, not only to avoid God’s wrath, but also for the sake of conscience. For because of this you also pay taxes. For the authorities are ministers of God, attending to this very thing. Pay to all what is owed to them, taxes to whom taxes are owed, revenue to whom revenue is owed, respect to whom respect is owed, honor to whom honor is owed. Owe no one anything except to love each other for the one who loves another has fulfilled the law.”

Dr. Peter Lillback:

Well, that’s the reading of God’s Word that forms the context of our study today. So let’s begin by just turning to our notes, which I said I will follow and summarize as we go through at various points. Ever since 1776, that’s obviously the birth year of our independence as Americans. Paul’s teaching on the civil magistrate in Romans 13 has offered a biblical context for interpreting the crisis between America’s colonial governments and the British crown in parliament.

Dr. Peter Lillback:

Both sides of the civil strife were compelled to explicate the apostles claims in Romans 13. As their controversy escalated from the stamp act of 1765 to the American Revolution birth in 1776. Simply put, did the quest for American independence violate scripture’s teachings? This study seeks to engage the main interpretive aspects of Romans 13, followed by a consideration of how the American founding fathers engage Romans 13 in their quest for independence.

Dr. Peter Lillback:

So again, just so you know, the big picture we’re going to take time and look at Romans 13 as a passage. We’ll try to understand some of the interpretive issues, the exegetical questions that it raises. Try to appreciate what is it trying to say to us? And then with that backdrop of a biblical study, we’re going to look at the history of how Romans 13 has engaged Western civilization, particularly as it led up to the American Revolution.

Dr. Peter Lillback:

So if you think about it, we’re going to be looking at biblical interpretation and then historical analysis. Those are our two big points today, okay? So now the second paragraph that I give to you is a quote from an article from the Scottish journal of theology that basically notes that the debate over Romans 13 doesn’t begin with the American Revolution. It was actually an issue that surfaced very much in the Protestant Reformation, because the Protestant Reformation was resisting established churches and kings to bring about a new expression of the Bible. And if they were defending their view from the Bible, what did they do with Romans 13 that’s in the Bible?

Dr. Peter Lillback:

How can you have a biblical reformation that creates protest against the king and then disregard what the Bible says in Romans 13? So it’s not a new issue with the American story. Rather, the reformation was the context in which the American Revolution will be birthed. It was a post reformation experience. Remember, the reformation 1517? It comes to its high water market about 1650. 1776 is just a century after the reformation has reached its crescendo point. It’s in the air. So this is not a new debate, and that’s important to remember.

Dr. Peter Lillback:

Now, as we go along, it says, “The debate over Romans 13 continues.” For example, Brian Fisher, a radio host with the American Family Affiliate rights. “It’s quite common in some segments of the evangelical community to criticize our war with England in the colonial era as a rebellion against God given authority and therefore a violation of Romans 13. For instance, noted expository preacher, John MacArthur,” for whom he says, “I have great or enormous respect.”

Dr. Peter Lillback:

He’s quoting MacArthur as follows. “So the United States was actually born out of a violation of New Testament principles, and any blessings God has bestowed on America have come in spite of that disobedience by the founding fathers.” And so Brian Fisher asks as he write, so I’ve gone and found the full quote of MacArthur. Let me read it so you can hear how he actually presents it here. So as we continue, MacArthur writes, “People have mistakenly linked democracy and political freedom to Christianity. That’s why many contemporary evangelicals believe the American Revolution was completely justified, both politically and scripturally.

Dr. Peter Lillback:

They filed the arguments of the declaration of independence, which declares that life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness are divinely endowed rights. But such a position is contrary to the clear teachings and commands of Romans 13:1-7. So the United States was actually born out of a violation of New Testament principles and any blessings God has bestowed on America have come in spite of that disobedience by the founding fathers.”

Dr. Peter Lillback:

Now, so there’s the challenge for us. Great Bible interpreters, expositors have said Romans 13 stands against what happened in 1776 in the American story. Is that correct? That’s kind of the context of our discussion. Now, a few backgrounds that I want you to appreciate is that we look at what we might call the old princeton, the old reformation reformed approach to understanding these issues.

Dr. Peter Lillback:

I’m quoting now a fellow who wrote an article from South Africa, from Northwest University named Gregory Bows. And he says this, “The following historic reform view of Romans 13, which might be called the political resistance view is clearly represented in Samuel Rutherford’s Lex Rex of 1644.” Charles Hodge, so he would be the great theologian of the old Princeton. By the way, S. Lewis Johnson loved Charles Hodge’s systematic theology. Often quoted it and appreciated. So that name has been heard at the chapel many a time through the years.

Dr. Peter Lillback:

So Charles Hodge in his commentary on Romans in 1835, while he didn’t follow through with it consistently also reflects this view in at least two statements. Hodge says, “Paul in this passage is speaking of the legitimate design of government, not the abuse of power by wicked men. In other words, Paul is not telling us what we need to submit to tyrants or any unjust laws. Paul is not talking about defacto rulers, those that are in fact claiming power presently. He’s not talking about God’s providential ordination or institution of government, but rather of the prescriptive or legitimate design of governance.”

Dr. Peter Lillback:

Now, what is he saying? Hodge is arguing that this passage is talking about what should normally be the role of government. It’s not looking at what happens when government is misfunctioning or misusing its power. Hodge goes on to comment, “No command to do anything morally wrong can be binding nor can any which to transcends the rightful authority of the power which it emanates. In other words, it’s not only the command to sin that we don’t have to obey when it’s issued by any would be authority, but further, we don’t have to obey anything coming from would be civil authorities beyond the requirements to act justly and to submit to justice.”

Dr. Peter Lillback:

Now, he goes on to mention here in this article that the great Westminster confession says that the magistrate is set up to support things that are lawful. So the question that’s in our minds is how do we interpret Romans 13? It’s very clear, it’s calling on us to stand and respect of authority. Authority comes from God, we must respect it. To resist it, is to this God.

Dr. Peter Lillback:

And then the question is that an absolute statement for which there are no exceptions? What was the purpose of the writer? Well, to dive down more deeply and more carefully, I’ve selected two great commentators that have written on the epistles to the Romans. One is William Hendrickson, and another one is John Murray. One of the founding professors at Westminster where I serve. And they make a similar point that Hodge made. Let’s try to follow the quote.

Dr. Peter Lillback:

Hendrickson writes, “Paul does not within the compass of these few verses give us a complete treatise on the respective rights of church and state.” He said, “Don’t expect this to be an exhaustive statement. He does not give us explicit answers to such questions as if the government orders me to do one thing and God through His Word tells me to do the opposite, what must I do?” And a question such as, “Does the moment ever arrive when because of continued governmental oppression and corruption, the citizens have the right and perhaps even the duty to overthrow such a government and to establish another in its place.”

Dr. Peter Lillback:

Said Paul is not addressing those sorts of questions. “Though the answer may well be implied in the statement that, ‘The one in authority is God servant to do you good.'” That’s Paul. And though the answer to the first question has been clearly stated by Peter in Acts 5:29. Do you remember what that says? That we must obey God rather than man. He’s saying Paul does not address that passage that was already known as part of the apostolic witness.

Dr. Peter Lillback:

Paul’s immediate interest then is to talk us in this passage about what is the normal pattern of good government? John Murray we’ll find will take much the same position. He says, “There are many questions which arise in actual practice with which Paul does not deal. In these verses, there are no expressed qualifications or reservations to the duty of subjection. It is however characteristic of the apostle to be absolute in his terms when dealing with a particular obligation.

Dr. Peter Lillback:

At the same time, on the analogy of his own teaching elsewhere or on the analogy of scripture, we’re compelled to take account of exceptions to the absolute terms in which an obligation is affirmed. It must be so in this instance. We cannot but believe that He would’ve endorsed and practiced the word of Peter in the other apostles. ‘We must obey God rather than men,'” Acts 5:29. The magistrate is not infallible nor is he the agent of perfect rectitude. When there is conflict between the requirements of men and the commands of God, then the word of Peter must take effect.

Dr. Peter Lillback:

Now, let’s try to distill this complicated pros in this keen insight. Basically, what he’s saying is let us remember that the writer, Romans is trying to tell us how we should look at government when it’s functioning properly. Whatever is being said in this passage must never be taken out of the broader context of the entire Bible. That’s called the analogy of faith or the rule of faith.

Dr. Peter Lillback:

One of the great statements we often hear is the only infallible rule for interpreting scripture is scripture interpreting scripture. We cannot take a passage on its own and say, “This is all there is to it.” So the point that Murray is saying in which Hendrickson then appealed to is that we have already the apostolic teaching that says when there’s a conflict between God and man, who should win the conflict? God should. That is not the view of this passage, but we must interpret that as part of the greater context.

Dr. Peter Lillback:

Now, we don’t have time to do this to full, but just an aside for a moment. This passage, of course, when it was read by great leaders in the Christian tradition of the West, they read it in its most absolute way and said, “This is the divine right of Kings. We’re established by Go,. You must obey us. Whatever we do is the law of God for you.” That is the great question. Is that what that passage requires of us?

Dr. Peter Lillback:

Now, to appreciate the historical context a little bit, that will help us to understand what Paul is doing. So this is our second point on page three, the historical context of Romans 13. The historical context is critical. Remember that the Jews had been expelled from Rome. The Jews were a difficult group of people because they didn’t follow the worship of the emperor. And you know what Christians were? They were essentially Jews that followed Jesus as the Messiah.

Dr. Peter Lillback:

And so there was already a hostility in the historic context of the Jewish people under the Roman emperor when Paul was writing. Subject to Rome, they had tension with their conquerors due to their monotheistic opposition to emperor worship and the loss of their previous political and religious autonomy. Remember, under the Maccabean revolt, there was an pendant Israel, and they’d lost their position. So Paul was writing now to Jewish Christians. There would’ve probably been some Gentiles, but by and large Jewish Christians in Rome.

Dr. Peter Lillback:

He understood the tensions with Rome. Yet he was a Roman citizen and had benefited from Roman law. His evaluation of the leaders was realistic as seen in Acts and in his inappropriate beating and imprisonment in Philippi and his subsequent appeal to Rome’s higher courts in the face of Jewish opposition to his Christian missionary activities. What do I mean by that? Do you remember when Paul got beat up in Philippi, he said, “I’m a Roman citizen.” And they were terrified. And they said, “We let you go.” He said, “No, no. You’re not going to let me go, you’re going to come and apologize to me because you broke Roman law and you are going to walk out of the city showing me out as an honored guest.” And then he dropped the issue.

Dr. Peter Lillback:

And of course, when Paul was taken under the persecution of the Jews, what does he do? His a Roman citizen, he appeals to Roman and he follows the law of higher appeal to the higher court. Paul says, “We want to follow the normal rules of government. We have rights as citizens. That should be our standard position.” And the context is, remember, we’re already viewed as people that are insurrectionists, that we don’t get along with at the emperor. We should try to follow government. That’s the historical context.

Dr. Peter Lillback:

Now, Murray will go on to explain this, we’ll just quote Murray here and we won’t read Hendrickson on page three. He says, “We know from the New Testament itself that the Jews had questions regarding the rights of the Roman government.” That as they realized Rome had conquered them that they have legitimate rights. But, “We also know that the Jews were disposed to pride themselves on their independence.” “We read also of seditious movements,” Acts 5. There were those trying to overthrow the Roman leadership.

Dr. Peter Lillback:

“There is also evidence from other sources, respecting the restlessness of the Jews under the Roman yoke.” “We’re told that Claudius had commanded all the Jews to depart from Rome,” Acts 18. “This expulsion must have been occasion by the belief that Jews were inimical to the imperial interests, if not the aftermath of Jewish insurrection. In the mind of the authorities, Christianity was associated with Judaism and any seditious temper attributed to Judaism would likewise be charged to Christians. This created a situation which was necessary for Christians to avoid all revolutionary aspirations or actions, as well as insubordination to magistrates and the rightful exercise of their authority.”

Dr. Peter Lillback:

What Murray is saying that Christians were a very small minority. They already had a negative reputation because of the Jewish opposition. And they had every reason to follow the law of the state to the highest level that their conscience would allow for their own security. There was a context in which they must in fact, be careful. Now, further we get dropped down to the bottom of the page. My third point is that putting Romans 13, not just in its historical context, but in its biblical context.

Dr. Peter Lillback:

Remember Romans 12 is the great chapter on the Christian’s duty to live in a community of love. So his discussion of government is going to be sandwiched into that very context. He’s been talking about as much as lies within you, “Live at peace with all men love must be without hypocrisy, let brotherly love continue.” And at the end of this passage, he’s going to say, “When you pay taxes, you’re fulfilling your duty of loving your neighbor.” You’re loving neighbor who’s the authority over you.

Dr. Peter Lillback:

So we want to keep this in mind, that part of his concern is to say, “Ideal government is an expression of a community where the rights of others are respected and love.” We read at the beginning of 0.3. “In Romans 12 Love is expressed as both individual and corporate Christian duties in the church.” If you go through Romans 12 with care, you’ll find some of the passage speak to you as an individual, and then will speak to all people in the plural. And it’s hard to follow that, but Paul is going in some passage saying, “You,” and then other times he speaks with a Southern accent and say, “Y’all.” Both are going on here.

Dr. Peter Lillback:

Now, that distinction is very important when we start looking carefully at what he’s doing in Romans 13, because some things he will say about you as a singular person, and then he will describe more broadly you as a group of people. And this creates a very important distinction that helps us to appreciate how we look at Romans 13. Now, I could go on more there, but let’s go to Roman numeral four for the sake of time, page four.

Dr. Peter Lillback:

So I want you to be aware then of some significant exegetical cues in Romans 13 that identify whom Paul is describing. Believe it or not in these few verses, there are seven different distinct entities that Paul is referring to. You can read it through and miss them all. But if you slow down and you read it with care, you’ll find that these seven different groups or individuals are identified. Let me read them.

Dr. Peter Lillback:

So number one, there’s going to be the individual Christian. You’ll be reading through Romans 13, and he’s talking as if he’s talking to you and to you as an individual. You as a person, a personal ethic is in view. Secondly, he’ll talk about the plurality of Christians, as members of the church in Rome, as a recipients of his epistle. So sometimes you as an individual, other times, they’ll say, “I’m talking to you people in the church at Rome, the whole group.” So there’s the singular individual, then there’s the entirety of the group.

Dr. Peter Lillback:

Thirdly, there’s going to be the individual, whether Christian or it. As he starts this passage he will say, “Let each soul.” In other words, anyone who’s alive. I’m not talking about whether you’re a Christian. This is anyone who breathes. I’m talking about a duty of every human being alive, whether they’re Christian or not. The individual, even if they’re not a believer. So that’s a third distinction.

Dr. Peter Lillback:

Notice fourthly, the whole class of rulers encompassing the highest leaders and the lesser magistrates who bear defacto authority. When we use the word defacto, we mean they’re in charge. [foreign language 00:25:19] means they have the right to be in charge. But whether they have the right to be in charge or not, they’re in charge, okay? So we can make a distinction, and that’s what we mean. In fact, they have the grains of government in their hands. So the whole class of rulers.

Dr. Peter Lillback:

But then fifthly, he will use it in the singular. He’ll talk about the individual ruler over an individual believer. He will say, “You in the place where you are and you come in contact with someone who’s in authority.” That’s kind like you and a police officer. Or it’s you and you’re going before a judge, it’s this relationship of one to one, an authority and you. So he has the individual.

Dr. Peter Lillback:

And what’s fascinating when he talks about the individual ruler over an individual believer, he will use two ecclesiastic terms. He will describe this ruler with the term deacon. He’ll do it twice. That’s the same word we have in 1 Timothy 3 about an officer in the church, the one who has the ministry of compassion and care, the deacon. We could call it the one who the ministers, the minister. Amazingly, that’s striking. A pagan authority is called a minister of God in the state, quite remarkable.

Dr. Peter Lillback:

But also, and after doing that twice, Paul will use another word. He will use the word liturgist. You know what a liturgist is? It’s one who gets up and leads the worship service. He follows. He’s the officer of worship. He’s up there saying, “Okay, sing this hymn. Okay, read the scripture. Pass that offering plate.” This is another position of leadership in the church being put precisely into the government. So the word deacon and liturgist are part of the original language. It’s remarkable, but there it is. And we can find that word liturgist when we trace it out in the Old Testament, Greek translation called a [foreign language 00:27:20]. It can be used of a priest, an official on the church as well. Now, here as an official in government.

Dr. Peter Lillback:

Sixthly, there’s a passage in our reading of these verses. There’s a group, a plural group who resists or acts against the ruler. It does not define who’s in this group. It may be Christians. It may be unbelievers. It may be mixed. It’s a group of people resisting. And then seventhly, there is the ideal leader who’s portrayed with his proper conduct. He’s the one that bears the sword to impose judgment against evil acts. He brings praise for good acts.

Dr. Peter Lillback:

Now, what I do in Roman numeral five is I take the Greek text, I give it to you. I know you all don’t know Greek, but at Believers Chapel, you never know. This is a highly educated group. Some of you read the original languages. I want you to see the singular and the plural are being used in regularly as you go through it. And what I’m going to try to do very quickly, because we don’t have time to do it. I give you the notes is that Paul is going to make the distinction between personal ethics and corporate ethics.

Dr. Peter Lillback:

There is a extraordinary difference between what we as an individual are called to do and what may be our duties as a group of people, okay? So there’s singular and plural. And Paul is careful to make these distinctions as he goes through this passage. So let’s take a look now as I’ll jump down to page five, verse one as you see and we’ll try to work through the exegetical part of this fairly quickly.

Dr. Peter Lillback:

Verse one, it says, ” [foreign language 00:29:02],” means every soul. You can hear the word [foreign language 00:29:06], we get psychology from that. The soul, every soul. So not just believers. The previous context as we noted of Romans 12 alternates between singular or plural, but all were believers in Romans chapter 12. But here, Paul now speaks of non-believers every single individual. He says that they are to come before the higher powers. The word higher powers means that there are those that are ultimate powers and there are lesser powers, to say the higher powers means there are lower powers.

Dr. Peter Lillback:

So we have the idea of the greater authority and the lesser magistrate. You have the one who’s a supreme ruler like the emperor. What about all the other ones under him? He’s recognizing there’s layers of authority. The rulers are plural. It’s not just a single monarch. In Rome, you’d say, “Of course, it’s the emperor.” No, there are higher powers. There’s the highest power, there higher powers than there are powers. There is a hierarchy. They are the higher powers. Those that rise above the surpassed individuals of the society, as well as lower powers as they rule.

Dr. Peter Lillback:

This implies that there’re various classes of monarchs and powers and opens the door for the recognition of what we call the lesser magistrate, the ruler who’s under a higher authority. And this whole hierarchy of power is for every soul. Every soul has to face this structure of government. Doesn’t matter what kind of government we have, whether it’s democracy, an aristocracy or if it is monarchy or whatever. We’re under various layers of authority and we’re to be subject. The word is, “Let him be subject.” This is a singular passive command. It means we are to bring ourselves into that, or if we’re not, we’re going to be put into it. The authority has a right to look at every single one and say…

Dr. Peter Lillback:

The authority has a right to look at every single one and say, “You have to be under authority.” This means submission to authority is the right of the authority to enforce and the duty of the rulers’ people to accept. This is why members of a realm are called subjects. Have you ever noticed that? What does the word subject mean? You’re under authority. You have to humble yourself and that’s the biblical pattern.

Dr. Peter Lillback:

Authority is of God and we are to see that we are under that authority, every one of us. We are placed under a higher ruler than us. This subjection here has the individual ethics in view. Each individual has a singular duty to be under the higher authority that is over him.

Dr. Peter Lillback:

Notice, it’s not talking about all of us as a state, all of us as a committee, said each of you whether you’re a believer or not, you have a duty to be under authority. No individual has the right to act against authority. Paul, as I said, is not addressing the question of corporate resistance to authority. This is the first key insight of this passage.

Dr. Peter Lillback:

This passage is basically saying no individual has the right to resist an authority on his own terms. What does that mean? John Wilkes Booth should not have tried to be an assassin and succeed in killing Abraham Lincoln. As much as we might love vigilantes, they don’t have a right to say, “I’m in charge. I’m going to take it into my own hands.”

Dr. Peter Lillback:

The assassin is said you should not ever take this authority into your hands. No one as an individual has a right to do this. This is personal ethics. It is our individual obligation to respect the authority that we’re under. Okay, further, why? For authority is not except from God. We translate it more fully. There would be no authority unless God had put this authority in place.

Dr. Peter Lillback:

Authority is a reality in general is in view, not any specific ruler, the whole concept of having authority is something that God has put in place. What does it mean? It’s not that some powerful person says, “I’m just going to be in charge and have lots of power.” No, it says that the person who steps up to lead has the smile of God upon him. Leadership is a God-given right. A leader is serving by God’s design. God is the one who created authority and who transmits it to the leader.

Dr. Peter Lillback:

If ruling is a function does not exist at all, unless it is from God. God is the creator of authority. The right to exercise, coercion, or power over another as a monopoly of a leader, by rulers flows from a grant from God. It is not inherent in the rulers themselves. It doesn’t come by conquest, pedigree or heredity. Ultimately, do you remember if you go back to biblical theology? Dominion was given to Adam. God said, “Rule.” That rule is something that God granted our very first father. Authority is a gift from God and all of us are responsible under that. We can call that the creation mandate. It has many other implications.

Dr. Peter Lillback:

Notice it goes on then as we continue on now at the top of page six, the next paragraph. And the ones that are, this is the idea, and the ones, now we’ve talked about authority in general, now, let’s talk about the ones that exist at this moment. The ones that are, the rulers existing at that moment, whether Nero, Pilate, Herod, they had, in fact, the right to rule because they were in a position that God had established for there to be authority and each individual had a duty to stand under them.

Dr. Peter Lillback:

Murray writes this, “Again, Paul does not deal with the questions that arise in connection with revolution.” Without question in these two verses, we’re not without an index to what we ought to do when revolution is taking place. The powers that be referred to the de facto magistrates, and in this passage as a whole, there are principles which bear upon the right or wrong of revolution but these matters, which become acute difficulties for conscientious Christians are not introduced in this passage.

Dr. Peter Lillback:

Now, let me summarize what he says, when he says the powers that be, he says when you find yourself under an authority, as an individual, whatever has happened to put that person in power, you have a duty to respect it, to the extent your conscience under God allows you to. Remember, you must obey God rather than man, but if there’s now a new authority. If a revolution has occurred and there’s a new leader, guess what? Your authority is, that’s our leader, it is the leaders that be. That seems to be the principle that when you’re under an authority, you now have a duty to respect it as an individual.

Dr. Peter Lillback:

Why? Because under God, they have been established or arranged or ordered. God’s providence has established all leaders at their times. This divine ordination means powers derived from God and is not an inherent possession of the ruler. It is true that humans create various forms of government. However, no leader is absolute as all rulers are under God.

Dr. Peter Lillback:

This then, is the biblical warrant for the American Pledge of Allegiance’s phrase, “One nation under God.” It says, “They have been established under God. The powers that be are in fact, God’s work and the individual, each of us have a duty to stand under him.” That in verse two, “Therefore the one, the singular individual who is resisting,” Paul is now drawing out the inference concerning resistance of government from the fact that authority has been established by God.

Dr. Peter Lillback:

Resistance is a temptation. In reality, wherever there is authority in a fallen world, the one who resist is singular. So still individual resistance of the magistrate is in view. It doesn’t matter whether you’re an anarchist in general or one who just simply doesn’t like his ruler, by God’s word, you have a duty as an individual under this ruler to respect the fact that God has put him there.

Dr. Peter Lillback:

The point now, as you see, it’s an individual, individual ethics. Now, drop down a little bit further to the second paragraph from the bottom under verse two, it now turns to the plural. Okay, it’s been individual all the way through. Now, we come to the plural. And so he says, “And the ones resisting.” So now we have a plural group of those are [inaudible 00:37:39]. Now, the resistance in view moves from singular to corporate, as the verb is plural and is in the active voice. It does not have the sense of I’m doing this for me, it’s something that I am doing.

Dr. Peter Lillback:

Thus, corporate resistance is in view that is done collectively for the general purpose of the group. While it is clear this group of individuals are resisting an established political authority, Paul does not expressly say here, that they collectively are resisting God’s authority, as he has just said in regard to the individual. Is that interesting? What was said about the individual is not said about those who are resisting in the plural. It’s this argument from silence, but it is significant. He does reiterate they are resisting God’s authority. He is recognizing that the group might have a unique purpose. What does he say in the next at the bottom of the page, they will receive to themselves judgment.

Dr. Peter Lillback:

Now, Paul does not say that as a group, they will bring on themselves judgment. Judgment is not specified as to whether it is coming from God or the ruler, both perhaps are in view. Those who choose to act against the ruler should recognize that there will be judgment coming for their act. If they resist the ruler, they must recognize that judgment is sure to come. Their effort had better be just and ready for counterattack from the leader.

Dr. Peter Lillback:

The word for judgment, we have the word krima. We hear that word in English as crime, from the position of the authority, he’s judged. This is bad. These groups are judging. When used, however, in the Greek Old Testament translation of the Septuagint, the idea means justice. It says, “They will receive justice.” Remember, justice is something that can have both, you deserve to be punished, or that you’re doing the right thing for the right reason. You will receive justice.

Dr. Peter Lillback:

Now, in the New Testament, the word tends to accent the idea of the word being an unjust act, that deserves some kind of condemnation, even the King James translates it damnation. King James wanted to make sure when you read that, that you’re going to go to hell, if you resisted him. He favored the strongest possible word, at least his translators [inaudible 00:40:03]. The word does not have to mean them. It means that there is going to be a judgment. It is actually a word that’s used to Jesus going to the cross. He was judged. Was he wicked? Did he deserve it? It was an unjust judgment.

Dr. Peter Lillback:

What we find in the plural here, it is not saying that you are resisting God, it says, “You will receive a judgment.” The question is, is it just or unjust? Now, there’s a lesser magistrate principle. There’s the right of a group to address the consequences they’re taking the act, something that no individual ever has the right to do but the plural group is still identified as this.

Dr. Peter Lillback:

Now, let’s continue. It says, “For the ones who are leading, this is plural and refers to those who are actively leading, “are not a tear or fear to the good work, but to the evil act.” This is the ideal view of government. When you are looking at a government, you would hope that these who are leading are pursuing the good but what happens if they’re not? That’s an honest question that we have to have.

Dr. Peter Lillback:

It’s singular, it says, “Do you will,” now, you as an individual again. It’s talking to you as a person. Do you in the singular, personal ethics. Do you want to not fear the authority? Whatever authority you have, the policeman, the local judge, the local police leadership team coming to you, respect their authority. They want you to do right. You are to call. If you don’t want to be afraid of them, do what is right. Do what is good. As an individual, do what is right and you will have praise of them as an individual. You receive praise from the leader.

Dr. Peter Lillback:

Here, the emphasis again, is on the personal rather than the corporate. Then, we find in verse four, “The minister or the deacon of God, he is to you onto the good. He is someone ordained by God, to be a servant to bring good to the people.” That’s why he bears the sword, and he is to judge the evil. The question that we come to at this point then is, normally this is what government should do but what if this one who bears the sword is using the sword to force you to do evil rather than good? Does that mean you just submit? That gives us both singular and plural question. It’s talking about the individual.

Dr. Peter Lillback:

This is where an individual has the right of civil disobedience, Acts 5:29, “We must obey God rather than man.” Well, the bottom line is, is that in the ideal form of government, as we will try to speed up and not go through the rest of you can read it, the leader is someone who is obliged to honor God with the good. As an individual, we must respect the authority. Judgment will come when we don’t. What about the plural group? That’s the question. That’s what then our founding fathers especially addressed.

Dr. Peter Lillback:

Let’s take that backdrop where I’ve tried to make the case, there’s singular ethics, there’s plural ethics, there’s a higher magistrate and a lower magistrate. We could keep going, but let’s, ideal government, it doesn’t address all things. Notice as we come to Calvin’s Institute’s as he deals with this matter. This is right at the end of book four of the institute’s, book four chapter 20, 31 and 32. This section now is how Calvin finishes his classic commentary on the theology of the Christian faith. He puts it this way as we begin reading on page 10, “But whatever may be thought of the acts of the men themselves, the Lord by their means, equally executed his own work when he broke the bloody scepters of insolent kings, and overthrew their intolerable dominations. Let princes hear and be afraid.”

Dr. Peter Lillback:

Okay, Calvin’s powerful words, what is he saying? Saying in the Bible, we find that God judges princes, and there will be judgment that God will bring upon them. Ultimately, that is our hope that God will judge the wicked leader, but that is not our only hope. Well, that is our normal hope.

Dr. Peter Lillback:

Notice as he comes to the middle of this paragraph under 31 what he says next with the word for when popular magistrates, it says, “For when popular magistrates have been appointed to curb the tyranny of kings, as the Ephori, who are opposed to Kings among the Spartans, are Tribune’s to the people to councils among the Romans, or Demarch’s to the Senate, among the Athenians and perhaps there’s something similar to this in the power exercise in each kingdom by the three orders. That’s, of course, his own France, when they hold their primary diets. So far am I from forbidding these officially to check the undue license of kings, that if they connive at kings when they tyrannized and insult over the humbler the people?

Dr. Peter Lillback:

I affirm that that their dissimulation is not free from nefarious perfidy, because they fraudulently betray the liberty of the people, all knowing that by the ordinance of God, they are its appointed guardians.” Again, powerful, big, English, classical language. What’s he saying? The whole history of Western civilization shows that there’s power at the top, and there are lesser magistrates under them, who have always been recognized as representing the people against the leader if he turns against the will of what is best for his own subjects.

Dr. Peter Lillback:

There are therefore these groups called the Ephori, the Tribunes, the Demarch’s and he mentions others in his own France. He said, “This is the whole story of Western civilization.” He says, “If they don’t do their job, they were put in places of authority. If they don’t do their job, they are wickedly sinning against the freedom that God has given for his people, that they are to defend.” Calvin is seeing, if you will, that lesser magistrate principle built into Romans 13, “It’s not the individual that has the right to resist power, but other authorities built into the system of government that are called to stand up and defend the people’s rights. Call that the lesser magistrate doctrine.”

Dr. Peter Lillback:

Now, we noticed in 32, let me just read a section of this, let me start at the top as against on page 10, “But in that obedience which we hold to be due to the commands of rulers, we must always make the exception they must be particularly careful that it is not incompatible with obedience to Him, to whose will the wishes of all kings should be subject, to his decrees their commands must yield, to His Majesty there scepters must bow and indeed how preposterous were it in pleasing men to incur the offense of him, for whose sake you obey men.

Dr. Peter Lillback:

The Lord, therefore is King of Kings, when he opens his sacred mouth, he alone is to be heard instead of all and above all, we are subject to the men who rule over us, but subject only in the Lord. If they command anything against him, let us not pay the least regard to it, but be moved by all the dignity which they possess as magistrates, a dignity to which no injury is done when is subordinated to the special and truly supreme power of God.”

Dr. Peter Lillback:

Calvin will go on and mentioned then that passage of Acts 5:29, what is he saying? That we must obey God rather than men and the lesser magistrate is precisely placed there by God’s structure for that purpose, so that our rights are protected, and our consciences can stand before Him.

Dr. Peter Lillback:

Now, whether you agree with the acts of Jesus that I’ve tried to give you, I want you to know that it is founded on a careful look at the text. No individual has the right to resist authority but collectively the group, do they? The answer is the Apostle said, “We will stand against them.” Calvin says, “That is the structure of government.” We’ve seen on page 11 then that Calvin holds to this lesser magistrate doctrine is Institute’s and we can define the concept very simply this way, “When the superior, a higher civil authority makes unjust, immoral laws or decrees, the lesser or lower ranking civil authority has both the right and duty to refuse obedience to that superior authority. If necessary, the lesser authorities even have the right and obligation to actively resist the superior authority.”

Dr. Peter Lillback:

Now, take a look at this next line. This is attributed to Emperor Trajan, a Roman emperor of the past. As he was assuming his authority, he said, “Use this sword against my enemies if I give righteous commands, but if I give unrighteous commands, use it against me.” What he was saying is I have authority to do what’s right but if I am violating the rights of what my own laws require, stop me. That’s your job. That’s the lesser magistrate. Nothing in Romans 13, as we’ve noted, takes away the right of a group to act. It takes away all individual rights to resist. All we can do is simply submit, and pray for lesser magistrates to defend our rights. It’s an interesting balance that reflects Romans 13. That’s the passage.

Dr. Peter Lillback:

Of course, now we begin to move into history. We see Calvin reflecting that, we see it principled and as Calvin has argued in the ancient tradition of the West, we find it in our own civilization, in the English speaking world with the great Magna Carta. Do you remember Runnymede in 1215 when King John of England was forced by the nobles to sign a document that limited his power? They said, “You cannot do what you’re doing. You’re violating the rights of the people.” They were exercising the right of the lesser magistrate to protect the rights of the people.

Dr. Peter Lillback:

John Knox, one of the great founders of the reformed tradition coming from Scotland, in his appellation written to the nobles of Scotland in 1558 cites many passages to support this doctrine. Knox wrote to the nobles because the Roman church had condemned him and burned him in effigy. He wrote to declare to the nobles as lesser magistrates, their responsibility in protecting the innocent and opposing those who had made unjust decrees.

Dr. Peter Lillback:

Knox made it clear, that it’s the duty of lesser magistrates to resist the tyranny of chief magistrates. When the chief magistrate exceeds his god given authority, or actually makes declarations which are in rebellion to the law of God, he exhorts the noble, so lesser magistrates in this document, “You are bound to correct and repress whatsoever. You know him to attempt expressly doing is repugnant to God’s word, honor, glory, or what you may aspire him to do against his subjects, great or small.” Then, there are many passages of scripture that he uses to appeal to this doctrine. You can see them listed here.

Dr. Peter Lillback:

Now, it’s fascinating all, I don’t put it here, in 2017, we celebrated the 500th anniversary of Luther’s his 95 theses. Do you know why Luther was able to post the 95 theses and live? It’s because Frederick the Wise, his leader, resisted Charles with fifth who said, “Turn him over. We need to kill the heretic.” He said, “No,” and he protected him. That was the lesser magistrate. The Reformation, as we know it, we would not be here today if there was not a lesser magistrate that said, “I’m going to protect the conscience of someone who’s trying to understand the word of God.” The whole reformation turns on this doctrine.

Dr. Peter Lillback:

Now, we consider another one. This is the classic book, Lex, Rex, that means law, king. I give you a picture of it here, the title page. This particular book was written by Samuel Rutherford, who was one of the commissioners from Scotland to the Westminster assembly. What he was seeking to do, was arguing that the King, who claimed to have all divine right based upon the passage of Romans 13, everyone had to submit to Him. He said, “No, there’s a law above the king. The king is not a law to himself. He is subordinate to a higher law. To that law, he must obey.” If he violates that law, he is violating his just authority.

Dr. Peter Lillback:

I read here, Lex, Rex, the political tract of the 17th century, Scottish theologian Samuel Rutherford, represents a particularly comprehensive, early modern justification for violent resistance against a political sovereign. Rutherford was a member of the party of the radical covenanters, who vehemently opposed the church reforms of Charles the First and when hostilities began, fervently supported the war against the king. This article explores the series of arguments, distinctions, and theological moves that Rutherford employs to incorporate Romans 13 as a central text supporting his pro-resistance argument. Romans 13 cannot be made to support the absolute right of a king. It says he is your servant to do good. The group has the right to recognize its duties be under that authority, and then under God.

Dr. Peter Lillback:

Now, there’s so much more we could say here about Scottish history. I won’t go into all of that but you’ll discover that one of the great phrases that we find in this period is we have no king, but King Jesus. That phrase will come from the governor’s to America that will begun to resist as they see their power being pushed. But let me go to page 14 and talk about what is called the Presbyterian rebellion. This now gets us precisely into Lex, Rex, the work that we have from Rutherford and the beginning of the preachers that were preaching in the day, talking about their rights of conscience before what they saw is the abuses of a king that was becoming a tyrant.

Dr. Peter Lillback:

On page 14, it’s says, “Some loyalists referred to the revolution as a Presbyterian rebellion after the Presbyterian church movement that came out of the Protestant Reformation.” What do we mean by loyalists? A loyalist was one who said we must obey the king. Of course, that is our duty as individuals but they had the belief that there was an absolute right to obey the king under any circumstances because of the Divine Right of the king, even if they thought evil had been done he’s still the king. You must obey them. That was the loyalists’ position that the king is absolute, authoritative in all things.

Dr. Peter Lillback:

The Presbyterian tradition coming under this disagreed. Let me read a little section here about Rutherford’s work. Perhaps you’ve seen Francis Schaeffer’s book, a Christian Manifesto. This book had a gigantic impact upon me about 30 years ago when I was beginning my ministry. Let me just read this section on Lex, Rex so you can see how he sees it as part of his understanding of the American experience.

Dr. Peter Lillback:

Schaeffer, of course, was a Presbyterian minister, so he represents the continuing idea of the Presbyterian rebellion against the tyranny of the king. He says on page 100 and following, “The governing authorities were concerned about lex, rex, because of its attack on the undergirding foundation of 17th century political government in Europe, sometimes called the divine right of kings. This doctrine held that the king or state ruled as God’s appointed regent, and this being so the king’s word was law. Placed against this position was Rutherford’s assertion that the basic premise of civil government and therefore law must be based on God’s laws given in the Bible.”

Dr. Peter Lillback:

As such, Rutherford argued all men, even the king are under the law and not above it. This concept was considered political rebellion and punishable as treason. Rutherford argued that Romans 13 indicates that all powers from God and that government is ordained and instituted by God. The state, however, is to be administered according to the principle of God’s law. Acts of the state, which contradicted God’s law, were illegitimate and acts of tyranny. Tyranny was defined as ruling without the sanction of God.

Dr. Peter Lillback:

Rutherford held that a tyrannical government is always immoral. He said, a power ethical, politic or moral to oppress is not from God, and is not a power but a licentious deviation of a power and is no more from God but from sinful nature and the old serpent than a license to sin. Rutherford presents several arguments to establish the right and duty of resistance to unlawful government.

Dr. Peter Lillback:

First, since tyranny is satanic, not to resist it is to resist God. To resist tyranny is to honor God. Second, since the rulers granted power conditionally, it follows that the people have the power to withdraw their sanction if the proper conditions are not fulfilled. The civil magistrate is a fiduciary figure. That is, he holds his authority and trust for the people. Violation of the trust gives the people legitimate based resistance, and he goes on.

Dr. Peter Lillback:

Let me show us then as we drop down in page 14 into the middle paragraph under letter B. “As such, one loyalist, Reverend William Jones, told the British government in 1776 that the revolution was instigated by Presbyterians, who are Calvinists by profession and Republicans in their politics, and that this has been a Presbyterian war from the beginning.” Another loyalist in New York wrote in 1774 about the Presbyterians, “I fix all the blame for these extraordinary American proceedings upon them. Believe me, the Presbyterians have been the chief and principal instruments in all these flaming measures.”

Dr. Peter Lillback:

American founder, John Adams, later in 1821, many years after the revolution reflected on and affirmed the influence of Reformed Christian political thought on the American founding, whether rightly or wrongly applied, the political principles of the American Revolution were, as Gary T. Amos observes in his defending the declaration, how the Bible and Christianity influenced the writing of the Declaration of Independence, “An inheritance left to colonial Americans by early generations of Christian writers. These principles included the people’s right of resistance, natural rights, and popular sovereignty, as opposed to the Divine Right of Kings and absolute rule. This heritage of Western political thought had developed over centuries, and laid the groundwork for the American Revolution, the founding of the new nation of the United States.”

Dr. Peter Lillback:

Now, as I finish up, my time is up and I want to open it for questions, let me just read a few final quotes that come from this era that show the thinking of those that were founders at this time. The men of Marlborough, Massachusetts unanimously claimed in January 1773, “Death is more eligible than slavery. A freeborn people are not required by the religion of Jesus Christ to submit to tyranny. We implore the ruler from the skies that he would make bare his arm in defense of his church and people and let Israel go.”

Dr. Peter Lillback:

Notice that most crowned governors, those who were appointed by the crown remained loyal to the king. One of them wrote to the Board of Trade in England saying, “If you ask an American who is his master, he will tell you he has none nor any governor, but Jesus Christ.” That’s the phrase, “No king, but King Jesus.” We find that running through the history.

Dr. Peter Lillback:

As we continue on, there are other examples that we can turn to on April 18, 1775. Now, this is a contested story, but it reflects this so I’m going to read it as a possibility rather than a fact. It’s Reverend Jonas Clarke, a Lexington pastor and a militia leader. When he was confronted by the demand to turn over the armaments of the militia and to surrender to the British troops, Jonas Clarke or one of his company said, “We recognize no sovereign but God and no King but Jesus.” That’s that covenanter cry, “No King, but King Jesus.”

Dr. Peter Lillback:

As you drop down at the bottom of the page to number six, “The Committees of Correspondence sounded the cry across the colony of no King but King Jesus. Jonathan Trumbull, a crown-appointed governor is the one who said, “If you ask an American who is his master, he will tell you he has none, nor any governor but Jesus Christ.”

Dr. Peter Lillback:

Now, if you turn to page 16, Patrick Henry, do you remember what he said? The man who said, “Give me liberty or give me death.” He said, “It cannot be emphasized too strongly or too often that this great nation was founded, not by religionists but by Christians, not on religions but on the gospel of Jesus Christ.”

Dr. Peter Lillback:

Samuel Adams, as he was signing the Declaration of Independence said, “We have this day restored the sovereign to whom all men ought to be obedient. He reigns in heaven, and from the rising to the setting of the sun, let his kingdom come.

Dr. Peter Lillback:

Notice, Mr. Meacham, a member of the House Committee on the Judiciary quoting many years later in the Congressional Record, he said, “Down to the revolution, it was deemed peculiarly proper that the religion of liberty should be upheld by a free people.” Benjamin Rush, one of the signers of the Declaration, he is a great Philadelphian declared this, “The only foundation for a republic is to be laid in religion. Without-“

Dr. Peter Lillback:

Foundation for a republic is to be laid in religion. Without this, there can be no virtue, there can be no liberty, and liberty is an object and life of all republican governments. And it described them self as follows: “I’ve alternately been called an Aristocrat and a Democrat. I’m neither. I’m a Christocrat.” And then Lewis Cass was an American soldier, lawyer, politician, and diplomat. After serving in the war of 1812, he became the Governor General of the territory of Michigan. And he stated this: “Independent of its connection with human destiny hereafter, the fate of Republican government indissolubly bound up with the fate of Christian religion, and a people who reject its holy faith will find themselves the slaves of their own evil passions and of arbitrary power.” That is this religion that says there is a law above the king, that can be resisted for what is right. Without that, we’re going to become subjugated.

Dr. Peter Lillback:

And then, finally, two other quick pictures. You see an appeal to heaven. You see the tree here? This is the first American flag on our ships. For all of you, navy men, I hate to say it, but George Washington, an army man, established the Navy. That hurts, I know, but it’s true. And his first schooners, there were three of them, they had this flag flying. This was the flag on those first three ships, An Appeal to Heaven. That is, if you will, the heart of the theology we’ve been talking about. It’s in our declaration of independence. We appeal to the Supreme Judge of the World. And what is that? That’s the theology of John Locke. You try to obey your government all you can. You appeal to their justice. You keep stepping back until finally you can do nothing else, but take up arms and appeal to heaven.

Dr. Peter Lillback:

This is John Locke, but do you know where John Locke got his theology from? His philosophy? They were family friends with the Rutherfords. He got it from Lex, Rex. Lex, Rex becomes the motif of John Locke, the politician, the political philosopher that was most read by our founders. And it’s captured in the very first flag of our schooners, An Appealed to Heaven. It’s in the declaration of independence. We appeal to the Supreme Judge of the universe. Philadelphia was the largest city in the new world. It’s where William Penn was. And he said, it’s so beautifully, as he put together his foundation for government, “Those people who will not be governed by God will be ruled by tyrants.” You know what that means? That Romans 13 is not an absolute right to a king to do what he will. When he violates that rule, will be ruled by God rather than man.

Dr. Peter Lillback:

So, this principle of what we’re interpreting is woven directly into the scriptures. And as I conclude and open up for questions, I want you to see that there are many things you can look at. The arguments of the declaration, the argument from how there was a biblical patterning of Judah, the Southern tribes and their difficulties with the Northern tribes, a whole host of sermons that were preached by great preachers, political books that are all before us, that we can learn from on your own study. I’ve given you the links to find them online. And I’ll just conclude by page 23 with this quote, and then we’ll open up for question. It says this: “A fitting conclusion to this study is to affirm that the American Founders understood Romans 13 and their quest for independence as entirely compatible.” They did not see themself as saying, “We have to just ignore Romans 13.”

Dr. Peter Lillback:

They said properly understood. It stands exactly where we stand. They were in full accord with a classic book called Vindiciae Contra Tyrannos by Stephen Junius Brutus. You may remember him, he was a Huguenot, one of the French Calvinists that were persecuted by the Roman Catholic Monarch. He wrote in his work, Vindiciae Contra Tyrannos, clearly read by many of our founders, this would’ve been one who believes in the five points of Calvinism. He was a good reformed Christian, a Calvinist through and through. And he writes this: “If God calls us on the one side to enroll us in his service, and the king on the other, is any man so void of reason that he will not say we must leave the king, and apply ourselves to God’s service: so far, be it from us to believe that we are bound to obey a king commanding anything contrary to the law of God, that, contrarily, in obeying him we become rebels to God.”

Dr. Peter Lillback:

And so, that was then, I believe, the heart of the American revolution. A firm appealed to Romans 13, that properly understood, limits the power of the king. It does not give him total powers. And yet it restricts any individual from becoming a vigilante and say, “I will assassinate the king, that I will bring the government in my own hands.” Rather, as we suffer, waiting for God to move, waiting for God to act, we pray that the magistrates who are under the highest authority will rise up and defend us. And then, we will stand with them as they seek to protect our rights. That’s precisely what happened in the American revolution.

Dr. Peter Lillback:

So, I have to humbly say, those that say that America was founded by disobedience to God, to say they don’t understand Romans 13. They clearly misunderstand the passion to obey God that motivated the reformation right from Luther, who said, “My conscience is bound by the word of God. Here I stand. God help me. I can’t do no other…” Do you know what he was doing? He was resisting all authority that said, “Renounce your books, burn your books, shut up right now or else.” And he said, “I will not do it. My conscience is bound by the word of God.” That has always been the position of authentic biblical Christianity. We will obey all authorities individuals. We will try to do our best as subjects, but if you cause us to choose between you and God, there’s no choice at all. We know what we must do and we will stand boldly. Okay. Let’s have some questions or announcements next.

Speaker 1:

Thanks Peter. That was really masterful.

Speaker 1:

I have so many questions that sum them up to one. The “Obey God rather than the men” context, obviously, is they’re forbidding evangelization, forbidding naming the name of Christ. The English crown was not doing that. I think we can all agree that Dietrich Bonhoeffer was justified on what he did, gainsay Adolf Hitler. So, in your study, how do the provisions of the Townshend Duties, the Stamp Act, the acceleration of tensions between 1765 and 1775, at what point, or was there a point, at which George III, not necessarily departed, George III, passed the point of into being unjust and tyrannical?

Dr. Peter Lillback:

Let’s go back to your first part of your question. The proper way to deal with Hitler was what World War II was all about. It was resisting as authority and calling on people to do it. So, I’m going to leave that as an open question. Now, maybe you’re right. He was justified if I know the full facts, but I think he took that into his own hands and said, “I’m going to try to kill Hitler.”

Dr. Peter Lillback:

Well, the question is, did he act properly with lesser magistrates? Did he do it with a proper authority or did he just do it as a… So, that’s the question I would raise. So that’s another a question for another time, because I’m not an expert in the details. I believe what happened with the colonial context. Is that, first of all, there was a constitution that was given to each of the colonies. The colonies had rights that were vindicated by the right of the king, recognized by parliament and established to separate governments that were self-governing. And, in that, they had the right to levy taxes. There was no provision for anyone else to do that. And so, people often think the reason the revolution happened is that people were mad, they had to pay some more taxes. So, they were getting all upset.

Dr. Peter Lillback:

Well, of course, nobody likes to pay higher taxes. That’s not what happened. They saw their constitution being thrown out the window. And that was the issue that one caused it to be unjust because a constitution is a mutual agreement between parties. Both sides have to agree to its ending. You can’t do it unilateral.

Dr. Peter Lillback:

Further, the king never spoke up to defend the people’s rights on the constitution. Parliament violated it and the king was silent. How long could that continue? Well, what was good is the Stamp Act got them through their protests to say, “We’re not going to do this.” But there was the Declaratory Act. The Declaratory Act said, “You know what? We’re going to give you the stamp act. We’re going to stop it. But I’m reserving my right to do whatever I want to do with taxes to you, whether you like it or not.” So, in other words, he took away the offense, but he maintained the egregious principle of saying, “I will violate your constitution when I choose.” He was already a tyrant at that act. Parliament aided and embedded the violation of the constitution. They had the right to their own.

Dr. Peter Lillback:

When I was doing archival research up in Boston, it was wonderful. I came across some early papers and there was a town hall meeting that had the following on it, “We hereby, as the members of this community, vote to tax London the following amount per head and we shall so issue the right that they must pay us X amount.” And, of course, that was ludicrous. But what they said is, “We have as much right to tax them as they have to tax us.”

Dr. Peter Lillback:

We laugh at that, but that’s the same issue. There was no authority. So the issue was not, “Oh no, I’ve got to pay more taxes.” It was, they are discarding the very constitutional right. It was sworn, it was covenanted and the king was duty bound to uphold it. In fact, when he’s backed off and he said, “But I’m going to reserve this right.” He was maintaining the right to, “I will tear up your constitution on this principle whenever I choose.” And by the time you get to the end of the declaration with all the grievances, they say, “Our courts are closed.” They’re going to take us from our own place and move us out of our place so we don’t have a proper care. All sorts of other principles of government are being removed.

Dr. Peter Lillback:

In other words, one thing after another was stripping the people of their constitutional rights. I wonder, how many of you would be upset right now if suddenly the bill of rights was saying that they’re gone, we don’t care. You no longer have those rights. I hope you’d have the courage to say, “We’re going to stand up and resist to that.” You mean I no longer have the right of conscience? You mean I no longer have the right to defend myself? You mean I no longer have a right to have a jury? Well, they were losing the rights.

Dr. Peter Lillback:

Perhaps, the most grievous one, which was they were posting regularly military officers in the people’s homes to enforce the laws they disagreed with and you had to take them in. Didn’t matter if they were going to take your jobs and your food and maybe tease or tempt your daughter or your wife. You had to do it. Even the home was violated. That’s injustice on its face. So, we let the king off the hook that right from the beginning he was supporting constitutional malfeasance, which was his duty. So, that’s how I begin to answer. Anybody else? Let’s go back here.

Speaker 2:

I guess you’re using a word that I’m not familiar with and, addressing the colonies relationship to the king, you’re saying constitution, or you’re saying there’s one document that governed all of the colonies?

Dr. Peter Lillback:

No, each proprietary colony or separate colony had its own charter or constitution.

Speaker 2:

There was franchising system from the king to…

Dr. Peter Lillback:

The one that I know most about would be the one that I’ve studied, which is the one that established Pennsylvania under William Penn. And so it’s called the Charter of Privileges and it’s fascinating. It begins and ends with a statement that no man can truly be free unless he is free within. And therefore, no one will ever be molested for conscience’s sake on religious matters in this colony. And he ends it with that. Begins and ends with that claim. And it’s that particular issue that’s so extraordinary. That, when the English king comes to power and he banishes Roman Catholicism throughout all his realms, the only place where the mass was legally celebrated was in Philadelphia, because of William Penn’s constitution, his charter, that said, “Here, no one will ever be violated.” Not even the king could end it. And so, now I’m not a Roman Catholic, but I believe in religious liberty.

Dr. Peter Lillback:

I thank God that the rights of conscience were protected. And William Penn had that constitution and it stood against the king. That should’ve been in every one of the colonies, because they all had their own royal charters that had a right for them to self-governance.

Dr. Peter Lillback:

Right here.

Speaker 3:

My question is about the English Civil War which was, of course about a hundred years before our civil war and how after King James and then King Charles, like you talked about the Scottish Covenanters, and they tried to force their own views and all that. The Puritan Parliament fought against the King’s army and defeated him and then accused him of treason against the people. So, is that kind of the same idea? The fact that the king… That treason wasn’t just against the king anymore, that the king could commit treason against the people now.

Dr. Peter Lillback:

So, there’s a whole theology behind this, so let me build a theology and then we’ll see how they got there. If you go back into the story of wicked queen, Athaliah and the child king, it’s in the kings, as you read the story, you’ll find that as the prophet now brings the new king to bear. The first thing he does, he makes a covenant with the king and with God. And then he puts the king in place and makes a covenant after the queen is overthrown with the people and the king. And so, the Puritan forebears, like Samuel Rutherford said, there’s a double covenant when government is established. Every king has a duty to be in covenant with God, and every king has a duty to be in covenant with the people. And by the way, the people, because they’re believers are also directly in covenant with God.

Dr. Peter Lillback:

And so, the theory that is developed is that, when the king violates his covenant with the people, he is violating his covenant with God. He’s a covenant breaker. The people, if they’re standing with God are still in covenant with God, they’re not rebels. They now have the duty as God-given subjects to stand against the king. Now, again, I’m going to be quite willing to say that maybe they did not have full grounds for what they did. I’m not an expert in the English Civil War. Maybe they went too far. Maybe they should not have beheaded him. That’s a great study in its own. But the theology, and the political science that they got from the scriptures and applied to the case, is that the king is not an absolute monarch that he can do what he wills. And he was exercising authority forcing people against their conscience to do things they believe were morally wrong.

Dr. Peter Lillback:

And he was enforcing it. And so he was creating all of this resistance. And, of course, the solution at the end of the day was religious liberty, but they hadn’t figured that out yet. It took the American story to do it. So, that’s the theology behind it. That was the basis of the civil war. They felt they had just caused because the King was forcing things against their conscience that they believe were wrong before God. And they said, “What do we do? Do we simply violate our conscience and sin? Or do we stand up and say we’re going to stop this man who now has become a tyrant.” Whether they should have beheaded him or not? I don’t know. That’s another issue. Back here.

Speaker 4:

I may be overlooking the simplicity of this comment, but, on page four, on the bullet seven of the significant accidental clues, number seven, “The ideal leaders portrayed with his proper conduct, he bears the sword to imposed judgment against evil acts.” Who defines the evil acts? Is it the biblical definition?

Dr. Peter Lillback:

That is the great challenge of a person. So, we would hope, and it would be our desire that a civilization would reflect biblical values. There was a belief going all the way back to the first century that generally there was a sense of what was right and wrong in a general sort of way. That we knew that if you stole it from someone, it was not right. That the idea of private property was honored, at least amongst citizens, against slaves no, we can take everything including your life, put you to work. So, what is evil and what is right is going to be defined by a society. And, when a Christian engages a society, he hopes that he will bring the core values of the 10 Commandments, for example, to bear in a culture. And that’s why, in the Western civilization in particular, it was very common to have the 10 Commandments and the courthouse walls, as well as in the church, you’d have the reredos in the church for worship, and then you’d have the 10 Commandments that would be all right there.

Dr. Peter Lillback:

So, for example, in the state of Pennsylvania, two things, I’ll tell you one, I was involved in the defense of a 10 Commandments plaque that was in the courthouse in Chester County. The free thought society said, “We need to take it down.” The commissioners, were there two Christians and a Jewish leader and they said, “We’re going to defend it.” I ended up being brought in as an expert witness in the court. I gave the historical argument and, in the appellate process, we won. And I’m thrilled that the judge said, “It’s because of the historical argument that we were going to keep this 10 Commandments plaque here.” So, in other words, the culture had defined it. It had been there for decades and it’s still there to this day. I’m very grateful for that.

Dr. Peter Lillback:

Now, another example of the law being part of the culture leaven by Christians, is in the Supreme court in Harrisburg and their chambers in the state capital building. Right behind where the justices sit. There’s a picture of Moses chiseling the 10 Commandments and the glory of God behind them. In a particular recent, about it’s been in the last decade, they took a picture of the court seated there and they airbrushed out the backdrop. They didn’t want to be identified with the 10 Commandments anymore. There was such a protest that was there and saying, “Are you abandoning that they had to get rid of the picture and redo it?” Now, they may repudiate what’s back there, but they’re still reminded every day, when they’re in ruling, that they are ruling under God. And so, you can think about the importance of this idea of gods creating right and wrong.

Dr. Peter Lillback: